by Ryan H. Flax

(Former) Managing Director, Litigation Consulting

A2L Consulting

Sometimes a trial graphic really does make the difference.

We can’t say that in each case we’re involved in, a trial graphic likely won the case or played a major role in the win. We support some of the best lawyers in the country and they use the tools we provide to do what they do at trial. Usually we’re there to make sure they do the best they can do, but sometimes we provide that key image or animation (and the associated consulting input) that really clicks with a judge or jury and enables the win. Here’s a recent example.

“Insert, Pivot, and Lock”

This was a patent infringement case before the U.S. International Trade Commission concerning the connection mechanism between automobile windshield wiper blades and wiper arms – that little piece of plastic that might as well be a Rubik’s cube for most of us almost every time we need to change our wiper blades. Our client held several patents covering a very special wiper blade connector that was being ripped off by a competitor. To win at trial (final hearing at the ITC), we had to get the judge to agree to our way of understanding the rather verbose patent claim language covering what was a simple, although elegant, invention.

Here’s an example of the claim language captured as an image from the patent:

Here’s an example of the claim language captured as an image from the patent:

I’d say that this is a challenging read, whether you’re a judge, a patent attorney, or a fast food restaurant cashier. It’s pretty technically complex and rather long. Definitely “lawyery.” No doubt that it satisfies the legal requirements for claim language, but it almost takes one’s breath away.

We needed to distill this language and the concepts behind it into something that was easily understandable, but we couldn’t be over-argumentative about it. Upon reading this claim language with the benefit of the rest of the patent’s disclosure and the reader’s own common sense, the invention had to seem simple (but elegant).

With that understanding, how do you do it?

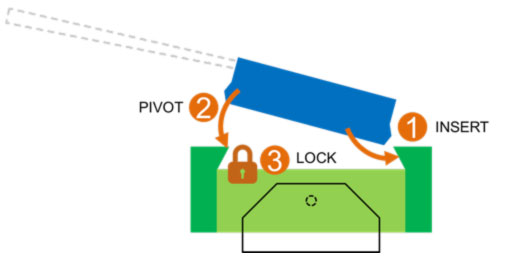

After a good deal of brainstorming with the litigation team, we found that the core of the invention was the configuration of elements that allows a user to join a wiper blade to a wiper arm by simply inserting the end of the wiper arm into the connector and then pivoting the two parts together so that they securely lock with one another. Easy enough to say, but it wasn’t so easy to actually identify this concept and explain it with any level of simplicity and specificity and persuasiveness.

After a good deal more brainstorming and whiteboard drawing, we developed a graphic design that really explained it. It was much easier to grasp the inventive concept and more convincing to show it visually, as follows:

With the animation above, we boiled down the claim language into something understandable by anyone, tangible, and acceptable for the judge. We can SEE it; he could see it. It makes perfect sense. The invention (and the infringing products) must work this way – of course.

It may look exceedingly simple, but I assure you it is not. It was not so simple to conceive as a solution to the obstacles in the case. It was not so simple to design conceptually. And it was not so simple to develop the 2D animation (all in Microsoft PowerPoint, I might add). It all works and worked perfectly.

After we showed this animation to the judge during the claim construction hearing, and after the accompanying argument, he eventually began reciting the tag-line of “insert, pivot, and lock” himself in addressing questions to counsel. A pretty good result to that point.

The results of the case were even better.

In the public version of Judge Pender’s Initial Determination (at 32), when discussing the claim construction, he titles one section “The End Portion of the Wiper Arm and the Connecting Element Can Pivot with respect to Each Other About the First Location Until Said Securing Portion Secures the Second Part of the End Portion of the Wiper Arm.” This illustrates that he really gets it. He doesn’t mention the insertion part here, but this part of his final opinion is devoted to the concept that after that insertion the two wiper system components pivot together to lock securely, just as the demonstrative shows. It is clear that the accused devices do this and equally clear that the prior art does not, so the judge’s recognition of this concept is critical to both making the infringement case and overcoming the opposing invalidity case.

In the infringement part of his Initial Determination (at 36 et seq.), Judge Pender identifies that the accused devices are assembled via a “simple pivoting motion.” Thus, in his finding, they infringe the patent’s claims. The claims cover “insert, pivot, and lock.” The covered product works by “insert[ing], pivot[ing], and lock[ing].” And the accused devices infringe because they, too, “insert, pivot, and lock.”

Winner!

Moreover, the animation above does more than establish that the wiper blades are connected by inserting, pivoting, and locking. It shows that this motion of locking can be engaged from either side of the wiper blade, that is, in a “toe-to-heel” or in a “heel-to-toe” insertion and pivoting. This was also crucial to establishing infringement by the accused devices (see Initial Determination at 40 et seq.). Judge Pender found that the respondent’s arguments that they couldn’t infringe because their products connected in a backwards sort of way compared to the complainants’ devices were just plainly erroneous.

The result of all these favorable events was a complete victory for our client. The judge found a violation of Section 337 and recommended that the commission issue an exclusion order against the opposing party, which will stop importation of the accused, infringing wiper blade products.

It is not my intention to minimize in any way the wonderful advocacy by our client in this matter. It was truly outstanding. I believe that counsel’s trial strategy combined with the effective demonstrative evidence really sealed the deal here. Seeing, in this case, was believing.

Other articles on A2L Consulting's site related to patent litigation and the use of visuals in patent trials, in the ITC and in IPRs:

- 21 Reasons a Litigator Is Your Best Litigation Graphics

- How I Used Litigation Graphics as a Litigator and How You Could

- 5 Tips For Inter Partes Review Hearing Presentations at the PTO

- Free Download: The Patent Litigation Toolkit (3rd Edition)

- Free Watch: Patent Litigation Graphics Secrets

- 11 Tips for Winning at Your Markman Hearings

- ITC Hearings: An Overview from Section 337 Practitioners

- 11 Tips for Preparing to Argue at the Federal Circuit

- Litigation Graphics and Demonstrative Evidence at the USPTO

- Trademark Litigation Graphics: Making Your Best Visual Case

- Other A2L articles discussing intellectual property litigation

Leave a Comment