Computer Graphics Key to $14.2 Million Med-Mal Verdict

August 9, 1999

August 9, 1999

By Eric T. Berkman

A Denver jury awarded $14.2 million to a 17-year-old girl whose physician failed to diagnose a condition that is common among those who receive bone marrow transplants.

As a result of the misdiagnosis, plaintiff Amy Bryan suffered severe damage to her lungs, liver and immune system, all of which shortened her life expectancy. She ultimately died from leukemia - the initial reason for her bone marrow transplant - several weeks after the verdict.

Plaintiffs' lawyers Keith Cross and Joe Bennett of Denver say that state-of-the-art computer graphics enabled them to overcome the defense trial strategies in an extremely complicated med-mal case.

"We had some of the best experts you could get, but we needed something more to make the jury understand their testimony," says Cross.

So working with New York-based Doar Communications, they put all their records and exhibits on a hard drive and hired a full-time computer operator to bring them up at relevant points during testimony. This was all projected onto a 10-foot screen.

By contrast, the defense utilized fiberboard posters "that kept falling over on the courtroom floor as they tried to stand them up," Cross adds.

"The jurors told us later that our presentation was much more organized and professional," he remarks. "They were impressed by the fact that when we had a witness on the stand talking about a particular medical record, the record popped up on the screen right away for the jurors to look at."

But Alan Richman of Denver, who represented the doctor, counters that jury sympathy - and not a superior presentation - was the overriding factor in this case.

"Amy presented very difficult [symptoms]," he says. "And I'm not sure the jury really understood [my client's] limited role and his recommendations for treatment."

Bennett responds that the plaintiff's team avoided playing to jurors sympathy. "We called no 'groaner-type' witnesses," he says. "And we asked for no specific amounts for pain and suffering - which is what you'd expect from someone trying to maximize the jury's sympathy for the client."

Despite their success with the computer graphics in this case, Bennett and Cross acknowledge that such a presentation is a costly endeavor, appropriate only for big-dollar cases.

"But I'd consider using it in almost any med-mal case because they're so difficult to win anyway, and you probably wouldn't bring one if you didn't think it was worth a significant amount," says Bennett.

Misdiagnosis

Amy Bryan, a California native, underwent a successful a bone-marrow transplant at a Stanford University hospital in 1995 when she was 13.

The transplant appeared to cure her leukemia and she was doing well eight months later, when her family moved to Colorado Springs, Colo.

After she moved, Amy was referred to a group called Childhood Hematologist /Oncologist Associates, known as CHOA. Amy's primary oncologist at CHOA saw her throughout the course of the following year and arranged for her to be seen by a member of his group, defendant Dr. Thomas Smith. Smith stated on his resume that he was the director of the pediatric bone-marrow transplant program at Presbyterian St. Luke's Hospital in Denver.

As it turns out, says Cross, Smith's title and purported expertise were based on having seen a half-dozen patients and having taken a two-week seminar.

"But all the experts who testified for us said that the fellowship you take to become a BMT specialist can last anywhere from one to three years," Cross remarks.

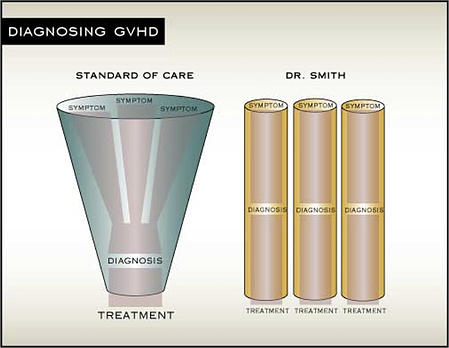

In early 1996, Amy began showing signs of "graft versus host disease" (GVHD), a common complication stemming from bone marrow transplants. It is a progressive disease in which the transplanted bone-marrow cells recognize the recipient's own cells as "enemies" and wage an assault on the body's tissues. Amy suffered an upper respiratory infection - a common "kickoff" for GVHD - and by the end of 1995, had begun to lose weight dramatically, according to her lawyers.

In spite of these warning signals, Amy's doctors weaned her from her precautionary anti-GVHD medications during this five-month interval.

Over this period, Smith saw Amy four times and apparently took no action in response to her weight loss and to what Cross characterizes as "alarmingly high" liver function tests. Meanwhile, Smith referred Amy to a business associate in Denver despite Stanford's recommendations that she be referred to Denver Children's Hospital, which had physicians who were experienced in diagnosis and treatment of GVHD.

Amy then "literally wasted away" as she spent another five months without a diagnosis, says Cross, noting that doctors blamed her weight loss on psychological problems.

In early November 1996, Amy lay close to death with severe lung complications and a "do not resuscitate" order. Finally her pediatrician sent her to Denver Children's Hospital, where doctors diagnosed her with GVHD within 24 hours.

But by that time, Amy had lost 80 percent of her lung capacity, had suffered severe liver damage and would be forced to spend the rest of her life in a wheelchair.

Amy's family subsequently sued Smith - as well as two other doctors involved with her care - in Denver District Court. The other two doctors settled for confidential amounts while Smith took his case to trial. Smith's primary argument was that he was not Amy's primary treating physician and had merely been "filling in."

At the conclusion of the two-week trial, the jury awarded Amy $14.2 million in damages. But because the jury found the two nonparty physicians 50 percent liable, the amount was reduced to $7.1 million.

The Silver Screen

According to Cross and Bennett, their computer-graphics presentation helped combat the defendant's strategies on several fronts.

For example, to rebut Smith's assertions that he'd thoroughly examined Amy, the plaintiffs' lawyers were able to project his records alongside the records of another doctor who examined her at the same time.

"It turned out that this other doctor had noted all kinds of symptoms that Smith had failed to notice," says Cross. "We blew the records up and had the jury see for themselves that it looked as if they weren't even examining the same patient."

Smith's attorneys also tried to convince the jury that Amy's parents were as much at fault as the doctors by not deciding to send Amy to Children's Hospital all along, as doctors at Stanford had recommended.

Bennett notes that he and Cross countered this with an electronic timeline that they displayed to the jury.

"We tried to focus on areas where we thought the defendant would blame the parents," he says. "And we were able to put together graphics to show why the parents didn't go to Children's Hospital, including Dr. Smith's resume where he claimed to be the head of a bone-marrow transplant program."

Bennett and Cross also assert that their computer presentation did a lot to hold jurors' interest through hours of ponderous scientific testimony. "For example, the medicine that's used for GVHD is so technical that if you just had a talking head up there with all these medical-science details, you'd put them to sleep," says Cross. "But we kept the jury's attention by having the testimony interrupted, so to speak, with graphic exhibits so they could actually see these things and listen to testimony at the same time."

Bennett adds that the jury could simply read along with the witnesses and that lawyers could pull out specific pages and notations and blow them up on-screen.

"If we had an expert talking a while and the jurors looked like they'd had enough, we'd just pop the exhibit," he says. "We even had a video of Amy's physical therapy session on the hard drive to show to the jury. And we had photos and documents embedded in our timeline so we could let the jury see what exactly happened on a particular day. Just click on the day, and the relevant document popped up. It all happened seamlessly. We'd never done anything like that before. It was awesome."

Richman, however rejects any assertions that his team was steamrolled by the plaintiff's presentation.

"The verdict was related to other matters," he says. "And the irony is that Tom Smith is widely viewed as a very competent, respected doctor whom Amy's parents initially wanted to use as her primary care physician. But his practice was based primarily in Denver and he wasn't as available as they required. We brought this up, but the jury apparently didn't process it."

(c) 1999 Lawyers Weekly Inc., All Rights Reserved.